As with any muse or love affair, the escapist is in danger of abusing escapism. One thing is certain: Escapism is a wild hirsute faerie, and it is up to the practitioner to tame it – because, unchecked, it will run amok and devour the innocent fauna that graze the mental fields of your daily life.

I, personally, have practiced various types of escapism, all of which produced mixed results. Yielding rejuvenating benefits to the mind, yet numbing my awareness of the present world around me.

In the vast field of psychology, for instance, the term “emotional detachment” refers to an inability to connect with others in a meaningful way, and escapism is often this condition’s best friend.

Escapism is also a means of muting the various symptoms of depression and anxiety that millions of individuals around the world suffer through daily. Entertainment industries and TV networks the world over make incalculable amounts of your money on your need to escape from a banal job; from an unhappy marriage; from a codependent relationship; from an evil step sister; from a bad haircut; from a receding hairline; from bad guacamole; from obesity; from a cancer screening; from the circus that is today’s politics; from boredom; from ennui; from a wheelchair; from apathy; from (ultimately) mortality.

Alchemists of escapism (the good ones, anyway) are exorcists of emotion – of the primitive, cathartic wildlings we hold chained and detained for fear of breaking with civility. Of going insane (more on that later).

Certain diagnosable disorders are blood cousins to escapism. Observe Exhibit A: Narcissistic personality disorder. Here, an individual may appear fully “operational” in relation to his/her environment, but – upon further inspection – proves only capable of connecting with a situation or person on a strictly intellectual level, whereby an emotional response would be more natural or appropriate.

Next, observe Exhibit B: Depersonalization disorder (DPD). Here, the sufferer is plagued with recurrent feelings of “derealization,” or the detachment of one’s perception from their motor functions. The term “remote control automaton” comes to mind. An out-of-body experience minus the near-death component. DPD is often seen as the nervous system’s defense mechanism against high levels of stress and anxiety.

For the adventurous types unfamiliar with the experience (and for that, you should feel thankful), I’d advise against experimenting with psychoactive drugs to emulate it. Instead, try reading Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway for about an hour, and when you get up to pee, or fetch a glass of water, the foggy headedness that concusses you as you stand and walk will give you the synecdoche of DPD you’ve been craving.

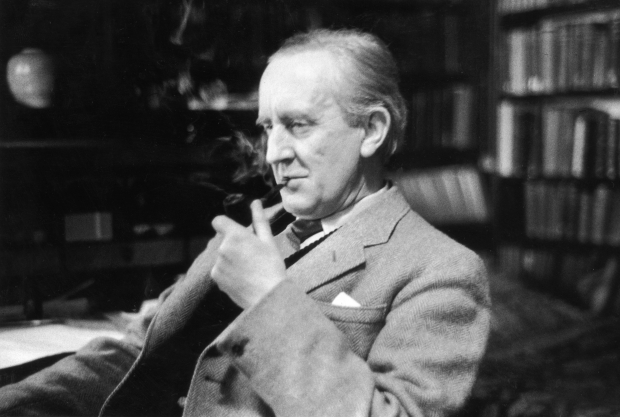

Still, escapism is much like coffee. As much as we have reason to fear its effects, we have reason to cuddle with it. Consider, for instance, the very catalyst of this post. It comes in the form of fantasy novelist and legend J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1947 essay, “On Fairy-Stories,” where a thorough argument is made in favor of the genre of fairy tales (and thus, escapism).

Here, he identifies a distinct irony in fantasy: That it permits readers to partake of their environment from the vantage point of an alternate reality, and thus review its moral imperatives, practices, culture and society from a safe perch – a process Tolkien referred to as “recovery.” Hence, in fantasy and escapism, the moral imperatives we take for granted are subject to question and scrutiny, and may even undergo positive change.

“Fantasy does not blur the sharp outlines of the real world,” Tolkien writes. “For it depends on them. As far as our western, European, world is concerned, this ‘sense of separation’ has in fact been attacked and weakened in modern times not by fantasy but by scientific theory. Not by stories of centaurs or werewolves or enchanted bears, but the hypotheses (or dogmatic guesses) of scientific writers who classed Man not only as ‘an animal’ […] but as ‘only an animal.’ ”

Still, if taken to extremes, escapism can be as dangerous as your garden-variety opiate. Social critics might even argue that the industries and corporations that profusely finance the “multiplex” business model of escapism are responsible for prioritizing fantasy above the betterment of the human condition. Escapism, in short, may enable our innate desire to embrace insouciance and thus ignore our problems (as individuals and as a nation).

Consider Karl Marx’s famous and oft-quoted opinion of religion, for instance: “[Religion is] the opium of the people” (see Critique of Hegel’s ‘Philosophy of Right’; 1843). Because he perceived religion as a man-made and “fantastic realization of the human essence,” Marx believed it produced the unhealthy illusion of happiness, rather than a boon for radical social change. Change he felt was especially needed in lieu of the socioeconomic injustices he attributed to capitalism.

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless people […] The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness.”

It’s creepy how well that quote works when you replace “religion” with “fantasy,” right?

Yet, as a self-diagnosed escapist, I reluctantly return to escapism as a means of stimulating social change (or even a positive change in my own life). To view the mundane with fantasy-colored glasses (something philosopher Edmund Husserl called “phenomenology”), one can fulfill a repressed wish; sate an otherwise unattainable desire; find resolution; transcend shortcomings; unabashedly experience hope; anonymously subscribe to a happy ending; liberate the spirit; or understand the misunderstood. Tolkien called this experience a eucatastrophe, which he heavily borrowed from the gospels of the Bible:

“God redeemed the corrupt making-creatures, men, in a way fitting to this aspect, as to others, of their strange nature. The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories […] and among its marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation.”

This brings me to an interesting article written by Micah White of AdBusters.org (February 23, 2011), titled “Learning From Jung’s Madness.” In it, White describes Swiss psychiatrist and analytical psychologist Carl Jung’s battle with insanity between October 1912 and July 1913, where he suffered from “waking hallucinations” of “macabre imagery of thousands dying in catastrophic floods.” Because Jung’s visions began in 1913, there’s little doubt they helped inspire his work on The Red Book (written between 1914 and 1930). The Red Book, or Liber Novus, was a personal compendium of Jung’s illustrations and calligraphic text, and the nascence of his theories on archetypes, the collective unconscious, and individuation. The book’s contents, in part, also describe encounters with a large black snake, and a guiding spirit he called Philemon.

White goes on to note:

“The first terrifying fantasy was accompanied by a voice that prophesied it would become real and Jung interpreted that on a subjective level, believing his personal world would soon collapse. For the next ten months [… ] Jung continued to be plagued by similarly dark visions of death, war, destruction, corpses and seas of blood. Alarmed by his deteriorating mental health, Jung privately feared he was descending into madness and diagnosed his situation as dire.”

On June 28, 1914 – amidst growing tensions between the great imperialistic powers of Europe – Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria (heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary) was assassinated by a Yugoslav nationalist. Within weeks of the assassination, the Habsburg ultimatum was issued against the Kingdom of Serbia, and the major powers of the world formed alliances that would lead to the First World War. “Swiftly,” White notes. “The world slid into chaos, sixty million Europeans were mobilized and an ocean of blood flowed from countless charnel houses.”

Following declarations of war, Jung became convinced of the prophetic nature of his apocalyptic hallucinations. To him, they weren’t the offspring of encroaching madness, but were, instead, divinatory visions that stood as evidence of a “collective unconscious, a shared cultural psyche that can become diseased.”

Anyone that’s taken a college course on the history of psychology is likely familiar with Jung’s theories on synchronicity and the collective unconscious. To Jung, these weren’t just theories … but personal testimony. As White notes, Jung’s story demonstrates “a false barrier between subjective and objective reality, between personal and societal insanity […].”

So, what does all this have to do with escapism and fantasy? Fantasy tales are fertile grounds for myths and archetypes. Prominent 20th century fantasy writers – as well as today’s bestselling contemporary fantasy authors – borrow(ed) from these traditions on behalf of the wondrous backdrops of their fantasy worlds (see Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings; C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia; then jump to George R. R. Martin’s superb A Game of Thrones series; or Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series). Myths and archetypes often go hand-in-hand with the technological, socioeconomic and sociopolitical climate of present times.

It’s a process of derivation Tolkien called mythopoeia, or “myth making.”

Mythmaking in of itself is an odd sociological phenomenon. In at least a couple instances in history, society (even religion) has resulted from the enthusiastic interpretation of fantasy or science fiction accounts.

Take, for example, Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1871 science fiction novel, Vril, the Power of the Coming Race, which told the story of a subterranean master race who perfected the control of a mysterious substance known as “Vril.” During that time, Bulwer-Lytton’s more enthusiastic readers took the accounts as real, to the extent that a sect of theosophists ordained the book as truth.

Since then, various theories formed to connect Vril – and the aforementioned master race – to the Wunderwaffen, or the “wonder weapons” of the Nazi regime, whose covert operations concerning weapons research during WWII are popularly attached to occultism and Vril-powered anti-gravity technology (see Die Glocke; see Nazi UFOs).

(If only Eddie knew what his book would do.)

The Vril Society first entered modern consciousness through Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier’s controversial 1960 book, The Morning of the Magicians, which served as a sweeping overview of various occult topics and alleged secret societies. As professional skeptic Brian Dunning of Skeptoid.com recently noted:

“[The authors] speculated about many mystical communities in Germany, among which was one inside pre-war Berlin called the Vril Society. The secretive Vril Society was said to be an inner circle among inner circles of various mystical, New Age, and occult orders. The book claimed the Vril Society formed the nucleus of the Nazi party. No reference to a Vril Society has been found documented prior to this book.”

Now, in terms of religion, I hesitate to draw attention to the relatively undisclosed beliefs of the Church of Scientology, which are based on the teachings of one L. Ron Hubbard (1911 – 1986).

According to Hubbard’s allegedly leaked writings from the 1960s (referred to as “Incident II”), the story of mankind’s life on earth began with the evil machinations of an intergalactic dictator known as Xenu, who (75 million years ago) apprehended the populations of his galactic confederacy. He cryogenized the bodies of the captured, and sent billions of them to Earth on spacecrafts that resembled today’s DC-8 planes. Xenu placed these bodies into volcanoes and detonated them, using hydrogen bombs.

The essences or spirits of these ancient races, however, survived and dispersed throughout earth (known as Thetans). Thetans are, essentially, the spirits that inhabit the human beings of today, carrying traumatic, repressed memories of the cataclysmic events first begat by Xenu. These traumatic memories are referred to as The Wall of Fire, or the R6 implant.

Sounds a lot like space opera fare, right? Interestingly enough, you won’t find any mention of Xenu or Hubbard’s space opera origin doctrines on the Church of Scientology’s official website, as it’s been speculated to be a sacred teaching reserved only for members of a higher order. It’s also interesting to note that Hubbard began his career as a pulp fiction writer of various science fiction and fantasy stories, before publishing his wildly successful self-help book, Dianetics (May 1950), which purports a metaphysical connection between the mind and the body. In this vein, an anecdotal relationship between Hubbard’s background as a pulp fiction writer and the events described in Incident II is plausible, albeit not conclusive.

The goal of citing Scientology in this post is not to imply that the tenets of its belief system are fraudulent, as any religion or movement requires an obligatory leap of faith. Consider, for instance, the numerous Protestant denominations and Anglican faiths that comprise the grand paradigm of Christianity, and the infinitesimal interpretations of its scripture by scholars, historians, readers and literalists of the Bible. One mustn’t forget the Creation Story in Genesis, either, which is comparatively fantastical.

Despite your stance on the material presented above, however, one constant appears to remain axial: Fantasy, myth, archetypes, religion and the innate human desire to escape our mortal coil are so inextricably interwoven into the fabric of modern consciousness that to actively remove it from the makeup of your everyday life might prove a disservice. Escapists and mythmakers alike grant free reign to observe and “reinterpret” the world – as well as their own lives – from a growing databank of alternate realities.

From my purview, this is a legitimately healthy practice for the mind and body – as it routinely quells the Wild Faerie within us all. But, as a veteran escapist, I’d only advise escapists-in-training one sticky caveat: Moderation is key. Take a break. Take a walk. See friends. Call your parents. Exercise.

The fantasies we absorb or create thrive best in tandem with our tangible lives, and we mustn’t lose grasp of that (lest we lose control, a la Jung). Escapism can turn on you like a wild animal, on a whim, and devour you whole. It can just as easily get in the way of life as it can enrich it.

As for the pragmatists, empiricists, behaviorists, hard scientists, and realists harrumphing on the other side of this article, I’d only encourage you to try looking at the lifeforms (microscopic and macroscopic), vistas and frescoes of this world with a child’s pair of eyes. Consider it another field experiment. You wouldn’t want to miss out on the beauty of small, novel details, or the wonder of fabled creatures, cryptids and impossible lands. Children can teach us a thing or two about the joy, fear and wonder of living.

Featured images taken from PublicDomainClip-Art.blogspot.com, NosContraMundum, Wikipedia.org, and various scans of The Red Book

This article shines like alchemical gold. Well done bro.

LikeLike

Thank you sir …

LikeLike

I love to combine my religious opium and my dark escapism-latte with flowing streams of intoxicating literature such as this one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

your compliment in of itself is literature! Thank you sir …

LikeLike

Though I’m very late in finding this article I have to applaud it and its author. It is very well written and could be a good start for a thesis, or at least used as a reference for a thesis. I’m also glad that Game of Thrones was mentioned and I wonder if a more detailed comparison can be made between the series and our current culture. I’m sure there can be, and I’d like to read it. Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi rcheckhamil, it took me about a year to respond to your comment, but I guess that’s the turtle’s pace at which I go about my brief days on earth! I think doing a cultural comparison piece with GoT would be quite a worthy endeavor, great idea.

LikeLike